On the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the first Impressionist exhibition – Paris 1874, I had the opportunity to revisit the work of these artists whose work I have always appreciated. I admit this must be the vanilla taste of art movements, but I embrace it. In particular, for as long as I can remember, I have been touched by Monet's series in which he depicted the same object in various weathers, seasons, or times of the day: water lilies, haystacks, the houses of Parliament...

La vie en bleu

Looking at Monet’s work also reminded me of my psychology of perception classes. I had heard that Monet suffered from cataracts he may have developed from old age, lead-based paints (Kean, 2022), or a myotonic dystrophy (Lane et al., 1997). In cataract patients, the lenses become clouded and opaque. This process degrades the quality of the visual signal; what’s more, they can also act as a filter preventing shorter wavelengths (i.e., blue) from passing through to the retina. This can result in a red and yellow tinted vision.

After cataract surgery, consisting in the removal of the opaque lens, colour vision typically improves (Mehta et al., 2020). However, in some cases, patients start complaining about seeing everything in blue. This side effect, also known as cyanopsia, occurs in 10% to 20% of patients when only one side is operated (Hayashi & Hayashi, 2006; Miyata, 2015) – as it was the case for Monet. This symptom tends to improve with time, possibly through perceptual adaptation (Chao et al., 2023). Cyanopsia can be interpreted as aftereffects following long-term yellow adaptation and/or the fact that the lens no longer filters ultraviolet light normally, letting them stimulate S cones on the retina (Kitakawa et al., 2009).

Following the operation, Monet retouched some of his pre-operative paintings. According to some rumours, he even sneaked into museums to correct his own exhibited work (Kean, 2022). However, he also complained vehemently about cyanopsia in his correspondence. “It’s filthy. It’s disgusting. I see nothing but blue” (Ravin, 1985). It must be said that he was very anxious before the operation, having seen other painters turn virtually blind from this (quite new) procedure (Gruener, 2015). He had only agreed to it when his vision was too degraded to carry on painting. The complaints about cyanopsia correlate with the start of a “blue period” in Monet’s work. Some authors (the first one seemingly being James Ravin, an ophthalmologist) later connected the dots: the blueish tones in Monet’s postoperative paintings must have been a consequence of his cyanopsia, just like the reddish ones of the preoperative period where due to his cataracts. As proof of the obvious, Ravin (1985) juxtaposed two paintings of the artist’s House from the garden representative of the two periods. Matvejev (2018) reports that they were actually painted by closing the operated or the non-operated eyes. Striking evidence that Monet’s perception of colours was altered by his condition…

The house from the garden, Claude Monet, circa 1923-1924; Monet wearing dark glasses after his surgery.

The Monet fallacy

… or is it? Does Monet’s blue period really demonstrate the consequences of his cataract operation on his perception? Let’s make a quick thought experiment to put yourself in the painter’s shoes. You are in front of your house in Giverny, set up a canvas, prepare your paint, and start reproducing what you see. Let’s say that one of your eyes has fully recovered from the cataract whereas the other eye suffers from cyanopsia. If you used your affected eye, the (blueish) paint would match the (blueish) scenery to you – but to an outside observer or to your healthy eye, both the house and the paint would appear in normal colours. At worse, the blue tints could lead to confusions between different colours, something similar that what you could expect with colour-blindness. Apart from these mistakes, an outside observer should not be able to tell whether you used your healthy eye or your affected eye to paint. In the same way, if we admit that Monet saw everything blue and painted what he saw, then the painting should not appear blue to an outside observer: Monet would not only see his house bluer, but also the very paint on his palette and canvas.

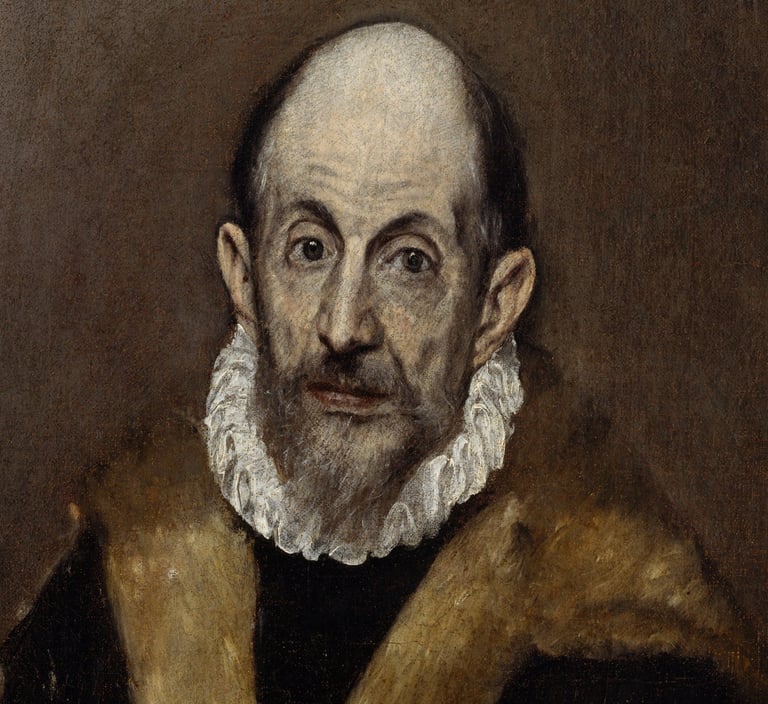

This common pitfall was coined the El Greco fallacy by Rock (1966; see Firestone, 2013). In that case, the elongated figures painted by El Greco were suspected to be due to astigmatism. Monet’s case may seem quite different, but it shares a common point: both the object that is being reproduced and the means of reproduction should be equally affected by perceptual distortions (Firestone & Scholl, 2014). This fallacy has concrete and important implications regarding the study of perception. For example, to establish cyanopsia, one should not ask a patient to rate on a colour scale how blue they perceive the world. The scale itself would be perceived with the same shift in blue and there should be not be any difference with a healthy individual (modulo the fact that the JND could depend on the blueness of the stimulus). That is why in the procedures used to assess cyanopsia, such a achromatic-point setting, the appearance of a stimulus is compared to an internal reference of what white is and not to a reference stimulus (Kitakawa et al., 2009).

Wrapping up: Why would Monet paint in blue?

Before we finish, I want to get back to Monet. His specific case is more subtle than it may seem. I think we should not remove the cataracts altogether when looking at Monet’s perioperative work. Before the operation, the degradation of the visual signal is not the subject of the El Greco fallacy. In fact, Firestone & Scholl (2014) briefly discuss Monet’s example: the El Greco fallacy applies to constant-error distortions, not to information loss. The corrections he wanted to apply to his preoperative paintings support this hypothesis.

On the other hand, cyanopsia cannot be the only explanation of Monet’s postoperative blue period. We saw that if his vision was bluer, the perception of the colours he used to depict reality should have been equally distorted and the canvas should be relatively unaffected. Art historians seemingly never really bought it (Doyle, 1985; Firestone, 2013). Why then would Monet be painting in blue? A range of factors may be at play, but I think they are well summed up by the fact that… Monet was an impressionist. His goal was not to reproduce a photorealistic view of the objects he painted. When Monet sees a sunset in Le Havre’s harbour, he paints the sun in a bright red amid the almost indistinguishable silhouettes of the boats (Impression, sunrise). It is a choice. Monet is completely capable of choosing neutral colours and sharper delineations (The entrance to the port of Le Havre).

Beyond cyanopsia and astigmatism, the El Greco fallacy can hide in many procedures based on perceptual judgments. Firestone & Scholl (2014, 2016) notoriously used the fallacy to put in doubt claims of cognitive influences on perception. For example, they analysed a study which asserted that morality could influence the perception of brightness (“as if thinking darker thoughts literally made the world look darker”). In the original effect, participants who reflected on their unethical past behaviour estimated on a numbered scale that the room was darker (Banerjee et al., 2012). Firestone & Scholl (2014) replicated the effect, but they also found the same effect when using a colour scale. If participants’ perception of lightness had really been the only explanation for the original effect, they should not have found any difference in this condition – the stimulus being assessed and its means of assessment should have been equally affected by the darkening perceptual bias.

The El Greco fallacy is a concrete application of the well-known abstract principle that perceptual judgments are not direct probes into perception. This is obvious in perception research, but other fields of psychology that rely on perceptual judgments may also suffer from the fallacy. Perhaps I will write another article on the El Greco fallacy in body representation research to share some thoughts I’ve been having during my PhD.

Monet is generally described as a master of colour theory. He reported labelling his tubes of paint and even disposed them in a regular order on his palette (Steele & O’Leary, 2001). Had he wanted to use expected, more neutral colours on the basis of his memories, he could have. He just chose not to. Impressionists work with and around constraints to render their impressions of things (Stokes, 2001). Monet’s – vocal – impression that his world had turned blue could have influenced his colour choices. Moral of the story: don’t mess with an impressionist’s impressions, or he will start painting everything in blue on purpose.